Art and Science: How collaboration could lead to a winner for Longitude Prize

23 Jan 2015

Written by Anna Williams

Since the Enlightenment there has been increasing specialisation in the respective roles of scientists and artists, which has fostered an image of the sciences and the arts as separated or even as diametrically opposed. Recently however, a sociological, historical and artistic re-analysis has revealed a shared underlying impetus in both fields to augment human knowledge and to extend our experience of the world. At its most basic level, this is demonstrated by the common desire within both fields to take pleasure from understanding something new and communicating this to others. And in many cases interdisciplinary collaborations have been a driving force behind the arts radically influencing the outcomes of science for the better.

Many people still see ‘science’ as purely empirical, embracing the quest for the production of truths, while ‘arts’ are considered an expression of the ‘metaphysical’, focusing on personal reflection on the human experience. Scientist and novelist C.P. Snow brought this to public attention in his 1959 lecture at Cambridge University entitled ‘The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution’. The lecture was a landmark in the history of the relationship between ‘art’ and ‘science’, and sparked a debate that continues today.

From science and art to ‘Sciart’

A major theme within the ‘sciart’ movement has been to bridge this perceived divide between the ‘two cultures’ of science and art. Notably, from the mid 1990’s the increasing popularity of sciart was reflected in growing encouragement for collaborations between scientists and artists through provision of funding from major institutions, including the Wellcome Trust, and the Sciart Consortium.

Rather than science and art collaborations being seen as extending our experience of the world and allowing for deeper moral discussions, we should ask what the practical implications of art and science collaborations are. The practices of art and science uphold different conventions. Often the publicly shared understanding of the ‘role’ of the artist and scientist are skewed. In some cases the way in which collaboration occurs between art and science has been shaped by the conventions of science, for example the need to gain funding through scientific institutions, and in others the conventions associated with the ‘free expression’ of the arts have influenced science.

Art and design in practice

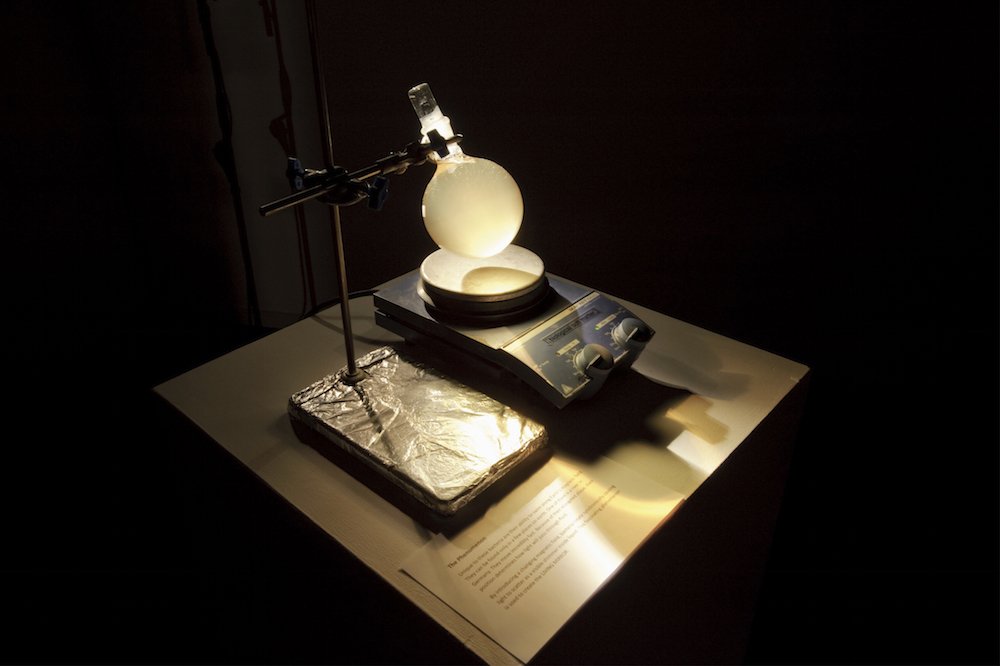

The boundaries between science and art are becoming increasingly blurred. The artworks from C-lab use synthetic biology as their medium. From genetically engineering bacteria to glow when they are stressed to creating bacteria capable of degrading material dye, C-Lab’s creations use the laboratory as their canvas. In this sense artists are adhering to the conventions of science through the use of lab techniques in order to produce artistic creations.

For innovators seeking to produce novel products for science, it is very interesting to consider how the ‘arts’ can disrupt or bring new insight to conventional science innovation processes. A good example of this happened through the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge collaborating with Longitude Prize research partner Science Practice. Designers at Science Practice were able to assist scientists in ‘seeing’ their data in a new light by developing new ways for scientists to visualise protein sequence bundles. Each individual sequence or group of protein sequences can be highlighted using different colours and easily compared on the same visualisation. The technique keeps individual sequences as intact, distinct lines, rather than separating and summarising the individual building blocks, so revealing patterns in sequential blocks that would be obscured by statistical methods.

New approaches, new perspectives

Sometimes the influence of art on science can be more subtle but just as important; using collaboration to get a new perspective. In an Arts Council England funded initiative, malarial scientists Dr Julian Rayner and Dr Oliver Billker worked with an experimental digital artist Dr. Deborah Robinson. Together they went to the clinics in East Africa that provided the blood samples for malarial research. The scientists became the photographer’s assistant, holding tripods not syringes, and seeing the community for the first time through eyes free to look more broadly at the issue of malaria. This collaborative influence is more difficult to quantify, however it is clear to see that art and science interactions can have a variety of effects from changing personal perspectives, to influencing how data is perceived.

For a successful entry to the Longitude Prize, teams should embrace interdisciplinarity and realise the potential that ‘sciart’ collaborations have to strengthen ideas. Truly novel innovation often happens in unexpected ways. The winner of Longitude Prize will have a novel diagnostic that has the potential to be game changing in the health care and surveillance sector – an artistic perspective has the potential to make a difference.