Tips from Vietnam: Designing technology to reduce antibiotic use and resistance

07 Jul 2018

Written by Vu Thi Quynh Giao

Working on a mobile application has made me realise how much our life depends on technological solutions, yet we understand so little about them. This is not so different from how antibiotics have helped enable a more productive society through better health – although few of us know how they came about.

An intervention package

In April, the Vietnamese Platform for Antimicrobial Reductions in Chicken Production (ViParc) contracted a company to develop a mobile application, whose purpose is to assess farming conditions under a 3-year study in Vietnam between 2016 and 2019.

Led by the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, with funding from the Wellcome Trust, ViParc is a randomized-control trial aiming to help farmers in the Mekong Delta raise healthy chickens using fewer antibiotics. This intervention package includes farmer training, regular farm visits, diagnostic support and non-antimicrobial alternatives. Our study discourages prophylactic use of antibiotics and instead emphasises good farming practices, which would minimise disease risks and thus reduce the need for antimicrobials.

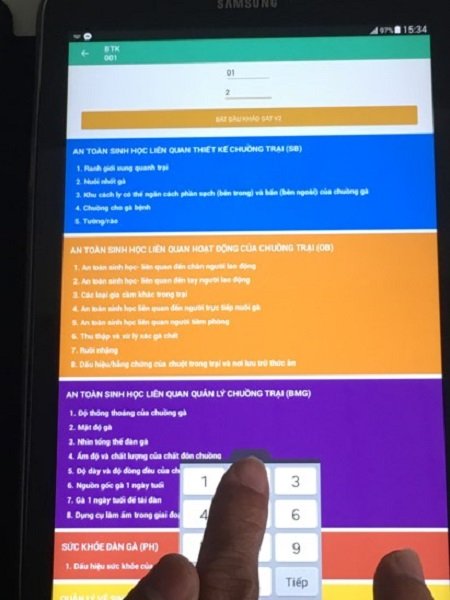

The application we have developed, “ViParc Auditing Tool,” plays a considerable role in improving farming practices: our veterinarians will use it to assess farming conditions and accordingly advise farmers on aspects ranging from biosecurity to feed management. With a set of questions and calculations pre-programmed into the application it will produce figures and charts on the spot, aiding communications between our veterinarians and farmers.

First version of the ViParc Auditing Tool

Not “just a technical thing”

Changing questionnaires from paper form into the binary 1-0-1-0 logic of coding for the platform, which I had thought of as “just a technical thing,” has proved complex. What was originally planned as a 45-day project has turned into three months now.

As someone from the client side I thought “the techies” would understand our needs immediately. But I was wrong. I learned rather late into the project that they did not have the contextual knowledge that was so obvious to me.

For instance, without knowledge of the standard chicken production cycle, the tech company organised our questionnaire into alphabetical order instead of in the context of the farming stages represented.

Due to multiple delays, it was tempting for me to pressure the tech company into an ultimatum: giving us a complete product, or terminating the contract. In the back of my mind though, I knew putting pressure on them could make our situation worse. So, I opted for closer communications with the tech company making an active effort to understand what was going on rather than externalising their coding process as “just a technical thing.”

Ms. Lang’s chicken farm

Different interpretations and learnings

Developing the ViParc Auditing Tool has taught me that in an age of expert systems, we need more – not less – involvement from laypersons, which oftentimes entails nuanced communications.

When we first tested the application in May, I travelled to the Mekong Delta province of Dong Thap, Southern Vietnam, and had the chance to visit a farm in our study.

“My husband told me everything he’d learned from the training,” said Ms. Lang*, referring to ViParc’s six-session course on good farming practices. “A vaccine must be reconstituted using a specific dilutent assigned by the manufacturer, not municipal water. The trainer taught that the fluoride in municipal water may have bad interactions with the vaccine.”

As someone helping with the course logistics, I got a kick out of hearing that our training had an effect beyond those that had attended in person. But my joy became short-lived.

“You should use municipal water to clean the chicken house and equipment such as this plastic drinker,” said one of our veterinarians, who had used the application to assess Ms. Lang’s farm on seven criteria, or a total of 30 post-vaccination questions. As the veterinarian talked, she pointed at a bar chart showing that the farm, using unprocessed water from a nearby river, scored low on hygiene and sanitation.

Ms. Lang added, “I thought municipal water was bad for vaccines, so it was bad for farming overall.”

It struck me that a piece of information from our training had been “decoded” in an unintended manner. We took this, however, as an opportunity to clarify to Ms. Lang that it was fine to use municipal water on the farm, but just not in the vaccines. The use of local river water is worse for the hygiene of the farm anyway!

What does success look like?

The encounter with Ms. Lang is another case that kept me wondering whether ViParc’s interventions will succeed if replicated in different sub-cultures of a country as small as Vietnam, which before 1975 meant more than one entity.

During the Second Indochina War (1955-1975), South Vietnam (officially the Republic of Vietnam) got its reserve of antibiotics mostly from the ally U.S., which happened to be the first country in the world to conduct mass production of penicillin.

North Vietnam (or the Democratic Republic of Vietnam), however, produced its own penicillin at a small scale in rural resistance bases, thanks to the techniques transferred by Dang Van Ngu, a Vietnamese physician who had studied in Japan and learned the American approach to growing penicillin-producing fungi in corn steep liquor.

What to make of this is that from the outside, Vietnam looks like a single system with a strong hierarchy ready for consistent policy implementation from North to South. But cultural differences across the country are so marked that in the old days, even antibiotics had their own South and North stories.

In the broader context of diagnostics, this is something to take into account when developing new technologies. My advice for anyone creating these types of diagnostics is to understand the cultures and environments you wish to use your test in, and work closely to ensure the people developing your product understand your aims.

*Name changed to protect farm privacy

Vu Thi Quynh Giao is a public engagement coordinator for the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Dang Van Ngu Street (Ho Chi Minh City) today, named after a physician pioneering penicillin production in North Vietnam during the Second Indochina War